Micron believes the 912 patent is invalid and dismisses the ruling from Gilstrap’s court. However, the Federal Circuit has already confirmed that district court rulings, backed by substantial evidence and expert testimony, carry more weight. When a district judge decides on patent validity instead of adopting PTAB’s suggestions, the district court’s higher burden of proof prevails.

Micron’s stance is merely a delay tactic. The PTAB’s preponderance of evidence standard is often flawed.

The 912 patent is valid and crucial. The PTAB only invalidated claim 16 based on its pre-2021 wording, but the rest of the nearly 100 claims remain valid after updates. Micron’s liability for the 912 patent spans just the last three years.

Historically, both the PTAB and the Federal Circuit have validated claim 16 and others multiple times. The PTAB’s recent decision contradicts NY case law and established precedents, and their opinion isn’t definitive. A patent remains valid until all appeals are exhausted if the PTAB suggests invalidity. Many companies can’t afford extended legal battles, but Netlist can and will pursue this to the end.

Micron’s stance is weak and likely to fail.

A director review is underway to address this, with a decision expected by July. While there is skepticism about the USPTO’s head, Kathy Vidal, correcting this, there is confidence in a federal appeals court seeing through the PTAB’s errors.

The PTAB’s actions have brought shame to its reputation. It wasn’t established until 2012, under an administration heavily funded by big tech, and continues to be influenced by major corporations like Samsung and Micron. This results in questionable decisions favoring these giants under the guise of economic stimulation.

Notably, Vidal, the current USPTO head, is still active in legal practice representing Micron, raising conflict of interest concerns.

To ensure true innovation and support for US companies, a shift in administrative policy may be necessary. Netlist’s technology significantly reduces energy costs and increases efficiency, posing a threat to Samsung and Micron’s business models. These companies would struggle without infringing on Netlist’s patents, impacting their profit margins substantially.

By 2028, Netlist’s royalties alone could reach $1 billion annually due to rising chip demand, excluding their direct sales. Netlist’s future is secure, driven by continuous innovation.

The USPTO’s granting of patents should be a final verdict, not easily overturned by a biased third-party system. The PTAB invalidates 80% of cases, reflecting its role in enabling big tech to exploit smaller innovators.

Protecting patents is critical to maintaining the US’s edge in innovation. Without stringent protection, the US risks falling behind.

The current scenario mirrors historical monopolies. Fighting for Netlist might seem daunting, but inaction ensures defeat. For justice to prevail, good people must act.

Let’s break down the above text into more straightforward language:

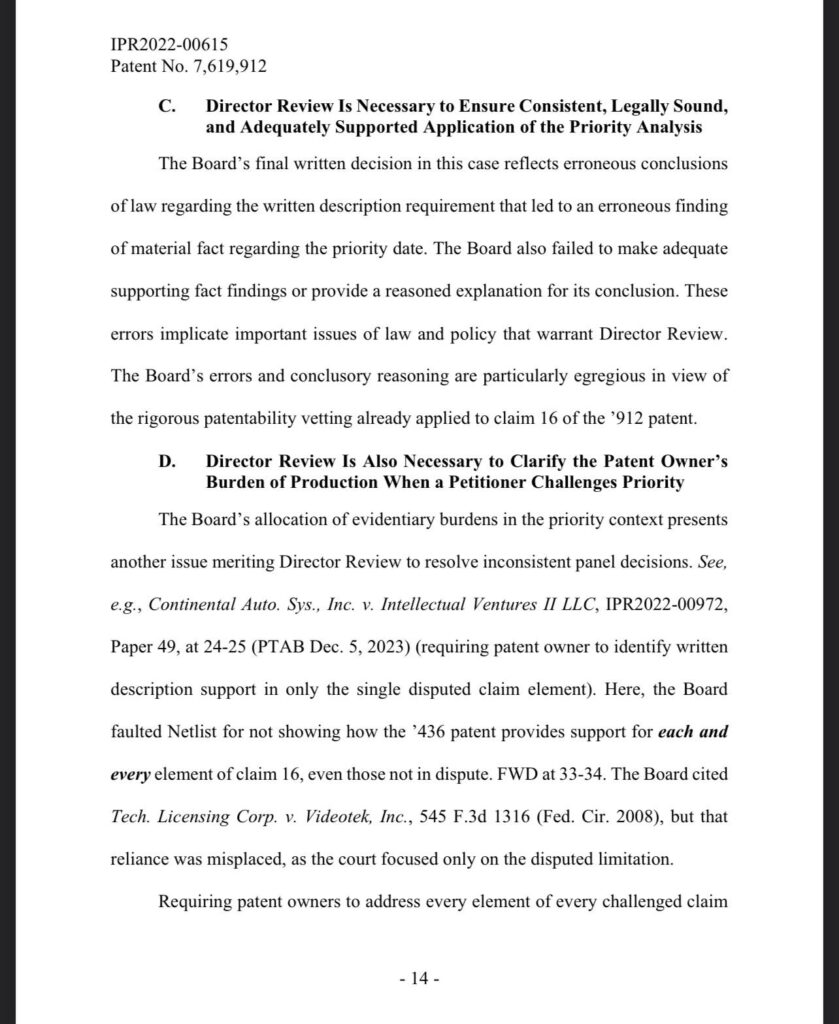

Introduction: The text discusses a legal issue related to the dates when a patent’s ideas were originally filed, known as “priority dates.” These dates are crucial in determining if a patent is valid during a review process called “inter partes review.” The issue needs a higher-level review (Director Review) to clear up some confusion about how to judge whether a patent was indeed the first to file its ideas.

The Problem: The board that reviews patent disputes made a decision based on the fact that the patent in question didn’t use two specific words (“bank address”) that appear in a newer patent claim. They argued that because these words weren’t used in the original document, the original patent shouldn’t be considered the first to come up with the idea. This is problematic because the rules say you don’t need to use the exact same words in your original patent as long as a person skilled in the field can understand that you were talking about the same concept. The board ignored this rule, which caused them to reject the patent’s claim to be the first.

Further Explanation: The text explains that the board’s decision conflicts with earlier court decisions (precedents) that say a patent doesn’t need to use the exact language in its original filing as appears in later claims if the concepts are understood by someone skilled in that area. Also, the board didn’t provide a good enough explanation for their decision, which is another error because decisions like these require clear, reasoned explanations.

Another Example: The board made a similar mistake with another patent date related to a different concept (“register”). They again focused incorrectly on the exact words used rather than understanding that the concept was known and used in the industry at that time.

Overall Issue: The decision-making process by the board has been flawed because they focused too much on the exact wording used in patent documents rather than understanding the concepts from the perspective of someone skilled in the field. This has led to possibly wrong rejections of patent claims which now need higher-level review to correct these errors and clarify the rules.

I CLOSE WITH THIS:

[a] patent need not teach, and preferably omits, what is well known in the art